On the morning of his thirty-first birthday, Josef K. is arrested by two men who eat his breakfast and cannot tell him what he’s charged with. He is not taken anywhere. He goes to work. He comes home. The trial, whatever it is, proceeds without him—or rather, it proceeds through him, feeding on his attempts to stop it. Kafka wrote that opening scene in a single night in August 1914, six weeks after the assassination in Sarajevo and three days after Germany declared war on Russia. He was also, that same week, breaking off his engagement to Felice Bauer for the first time.

The conjunction matters. The Trial is not about bureaucracy in the abstract. It’s about the specific horror of a man who believes, somewhere beneath his panic, that the charge against him might be real—and who cannot ask what it is because naming it would confirm it. Every procedural absurdity K. encounters, every painter and lawyer and cathedral priest who offers to help, is an escape route that leads deeper in. Kafka understood that mechanism from the inside. He had spent years in it.

What he finished in those months of 1914 and 1915—he never declared the novel done, left chapters in a drawer, told Max Brod to burn everything—was not a political allegory but something closer to a portrait of guilt that has outrun its cause. Josef K. doesn’t know what he did. Neither do we. That is not a mystery to solve. It is the condition of the book.

The Man Who Administered His Own Sentence

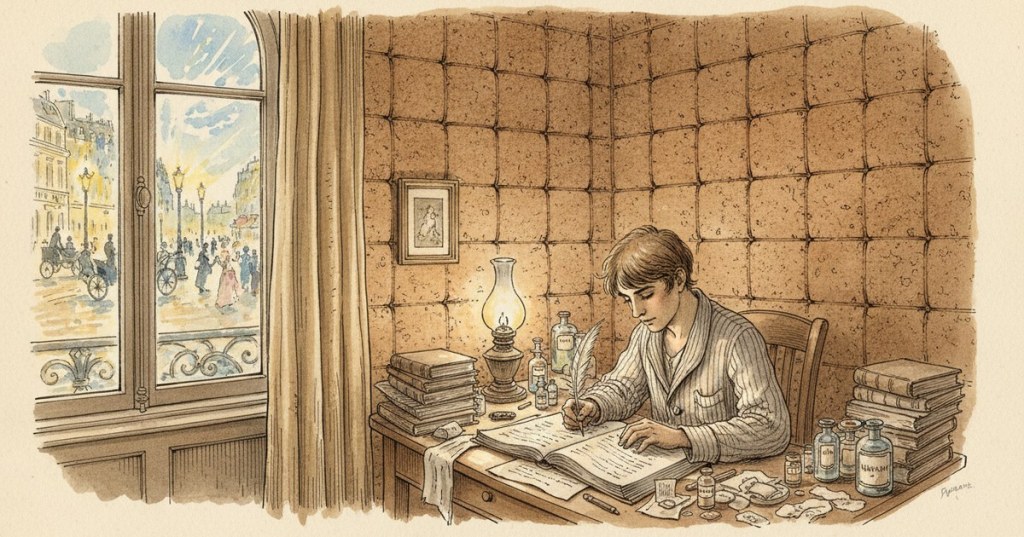

Kafka spent eleven years as a senior claims officer at the Workers’ Accident Insurance Institute in Prague, assessing industrial injury compensation for men who had lost fingers, hands, whole limbs to machines their employers had not bothered to guard. He was good at it. He wrote meticulous reports, proposed safety reforms, understood bureaucratic machinery in the way a mechanic understands an engine—by having spent years watching it fail people. His literary reputation has often turned him into a pale, tubercular visionary isolated from the world, but the biographical record is more uncomfortable than that: he was competent and embedded, and he hated that he was.

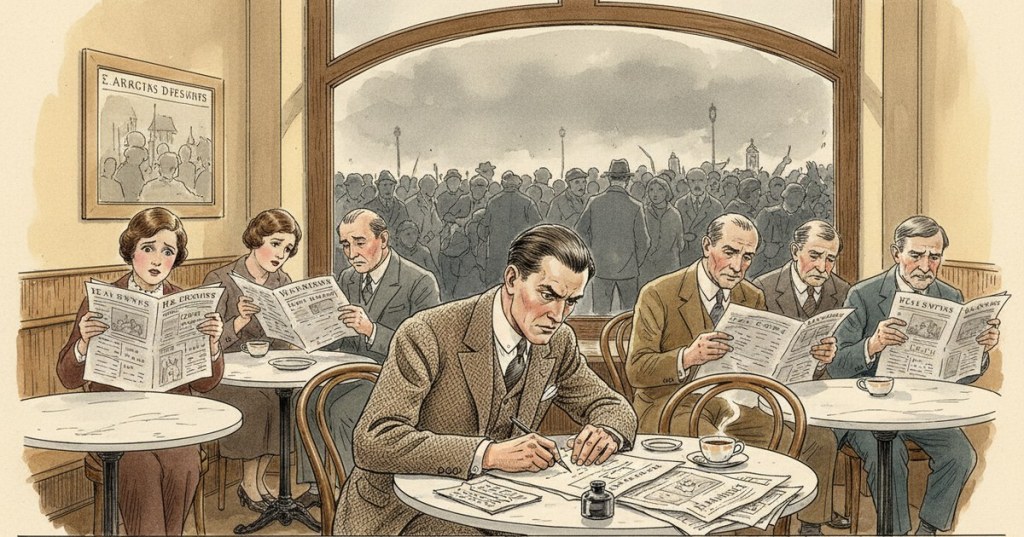

The engagement to Felice lasted, in its fractured way, from 1912 to 1917. In his diary entries from those years, Kafka describes writing as the only thing that gave him the right to exist, and marriage as something that would extinguish writing, and the inability to choose between them as a kind of permanent verdict. When he writes, in The Trial, about a court that operates in attic rooms above ordinary apartments—that holds its sessions in buildings where families are also cooking dinner and children are doing homework—he is not imagining Kafkaesque abstraction. He is describing what it feels like to carry a proceeding inside you while the world continues its ordinary operations all around you.

He was diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1917, the year he finally broke the engagement for good. He died in 1924. He was forty. Max Brod published The Trial the following year, against explicit instructions. Whether that was friendship or betrayal is a question the novel, characteristically, refuses to answer.

What the Court Already Knows

The genius of the novel is not its surrealism—it is its precision. The court’s logic is not random; it is perfectly consistent, internally, once you accept its first premise: that accusation and guilt are the same thing. Every character K. consults confirms this premise while appearing to contest it. The painter Titorelli explains with cheerful expertise that acquittals are theoretical. The lawyer Huld explains that the most effective strategy is to avoid annoying the lower clerks. The priest in the cathedral explains that the doorkeeper in the parable was not cruel—he was only doing his job. Each explanation is coherent. Each one closes another door.

What makes the novel land, still, is that K. is not passive. He fights. He organizes. He drafts a petition. He fires his lawyer and decides to represent himself. His energy and intelligence are completely genuine, and they are completely useless, and Kafka is not cruel about this—he is something worse than cruel, he is accurate. The final chapter, where two men in frock coats arrive at K.’s apartment on the eve of his thirty-second birthday, is four pages long and written with the flat procedural clarity of an official report. K. does not resist. He has been preparing for this since the first page, and so have we, and when the knife turns, the sentence Kafka gives us is not dramatic. It is administrative. That economy is the whole argument.

Why This Translation

Kafka’s German is not ornate. It is the language of forms and memos—precise, impersonal, faintly polite—turned toward material that strips politeness to its skeleton. A translation that reaches for elegance misses the point; one that flattens into plainness loses the constant, quiet pressure of a bureaucratic register being used to describe a man’s destruction. This edition holds that tension. The sentences read the way official correspondence reads when you know it contains something terrible: smooth on the surface, load-bearing underneath. If you have not read The Trial in English before, or if you read it in a version that felt distant or dated, this is the edition to go back with. Find it here: The Trial: A New Translation.

The court, the novel insists, was always already in session. You were just the last to know.