Dostoevsky’s Most Famous “Holy Fool” Falls Into Society’s Trap—Here’s Why The Idiot Still Hurts

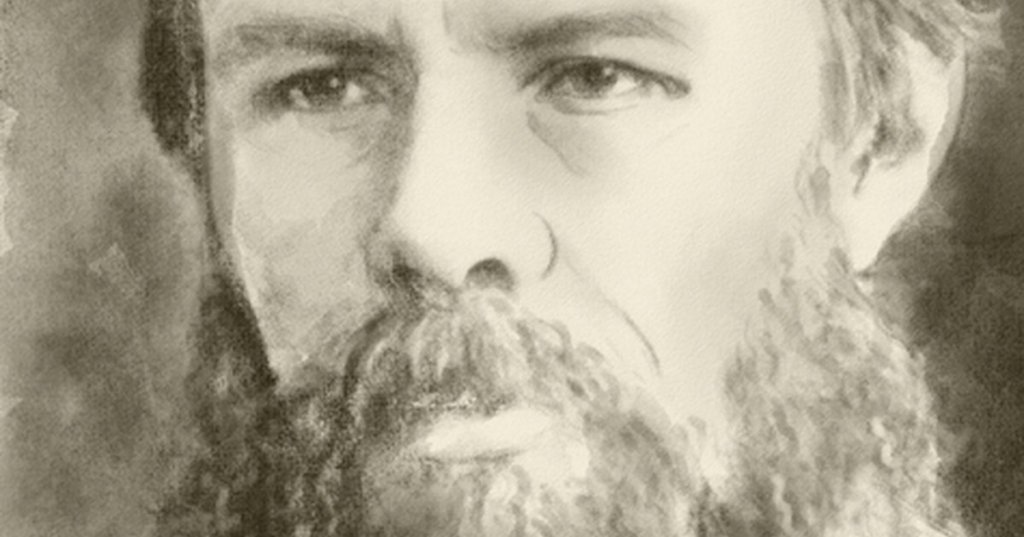

Who Was the Author?

Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821–1881) was born in Moscow on November 11, 1821, the son of a doctor who worked at the Mariinsky Hospital for the Poor. He trained as an engineer at the Main Engineering School in St. Petersburg, but literature pulled harder than mathematics. His debut novel, Poor Folk (1846), made him briefly famous in the city’s literary circles—then, almost as quickly, he became a target of gossip, criticism, and his own volatile temperament.

The turning point came in 1849. Dostoevsky was arrested for involvement with the Petrashevsky Circle, a group that discussed banned ideas and criticized serfdom. After months in prison, he and others were taken to Semyonovsky Square in St. Petersburg for a mock execution—an event he later described as psychologically shattering. At the last moment, the death sentence was commuted to hard labor. He spent four years in a Siberian prison camp in Omsk (1850–1854), followed by compulsory military service in Semipalatinsk, experiences that fed directly into the moral intensity and claustrophobic social pressure of his later fiction.

Returning to St. Petersburg in the 1860s, Dostoevsky wrote under financial strain, personal grief, and worsening epilepsy. He married Anna Snitkina in 1867, and the couple traveled through Europe for several years, often running from creditors. It was during this period—after the success of Crime and Punishment (1866) and before the later peaks of Demons (1872) and The Brothers Karamazov (1880)—that he wrote The Idiot (first published 1868–1869). He died in St. Petersburg on February 9, 1881, leaving behind novels that still feel less like stories and more like storms you walk into.

About This Book

The Idiot is Dostoevsky’s daring experiment: what happens if a genuinely good person enters a world trained to mistrust goodness? Prince Lev Myshkin returns to Russia after treatment in Switzerland and is dropped into a St. Petersburg society that runs on status, money, rumor, and performance. Myshkin’s openness reads as naivety; his compassion looks like weakness; his honesty becomes a kind of social provocation. Around him swirl fascination, desire, cruelty, and the sharp-edged comedy of people trying to appear superior while quietly falling apart.

Why does it matter? Because the novel refuses the comfortable idea that virtue automatically “wins.” Dostoevsky stages goodness as a disruptive force, not a decorative one, and asks what a culture does when confronted with someone it can’t easily categorize as predator or prey. The book also captures a 19th-century Russia vibrating with modern anxieties—social mobility, financial precarity, the hunger for spectacle, the fear of being laughed at. If you’ve ever watched a group punish someone for being sincere, or seen kindness treated as a trick, this novel won’t feel like a museum piece. It will feel like a mirror.

Why Read a Modern Translation?

A modern translation matters with The Idiot because so much of its power lives in voice: the quick shifts from irony to tenderness, the social “noise” of conversations, the way a sentence can turn from polite to predatory in half a breath. Older translations can flatten that energy into stiff formality, making characters sound more alike than they are. A new translation can restore the novel’s speed, its awkward pauses, its sudden heat—helping Myshkin’s gentleness land as lived human behavior rather than saintly abstraction, and letting the book’s humor and menace share the same room the way Dostoevsky intended.

This Edition

This post contains affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases.

Leave a comment