He Was Europe’s Most Read Writer—Then He Vanished: Why Stefan Zweig Still Hits Hard

Who Was the Author?

Stefan Zweig (1881–1942) was born into a comfortable Jewish family in Vienna, then the glittering capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He came of age in the last years of imperial Europe—cafés, concert halls, newspapers, and the sense that culture could knit nations together. Zweig studied philosophy at the University of Vienna and began publishing early, moving easily through the literary world as a poet, essayist, and translator. By the 1920s and 1930s he was one of the most widely read German-language authors on the planet, known for psychological precision and a gift for making private emotion feel like public history.

That career collided with politics. Zweig was a committed European humanist and a pacifist shaped by the trauma of World War I; he believed nationalism was a cultural illness, not a destiny. When the Nazis rose to power, his books were banned and burned in Germany, and his position as a prominent Jewish writer made staying in Austria increasingly untenable. He left Austria in the 1930s, lived in Britain for a time, and eventually crossed the Atlantic, watching from exile as the world he loved—cosmopolitan, multilingual, optimistic about art—was dismantled.

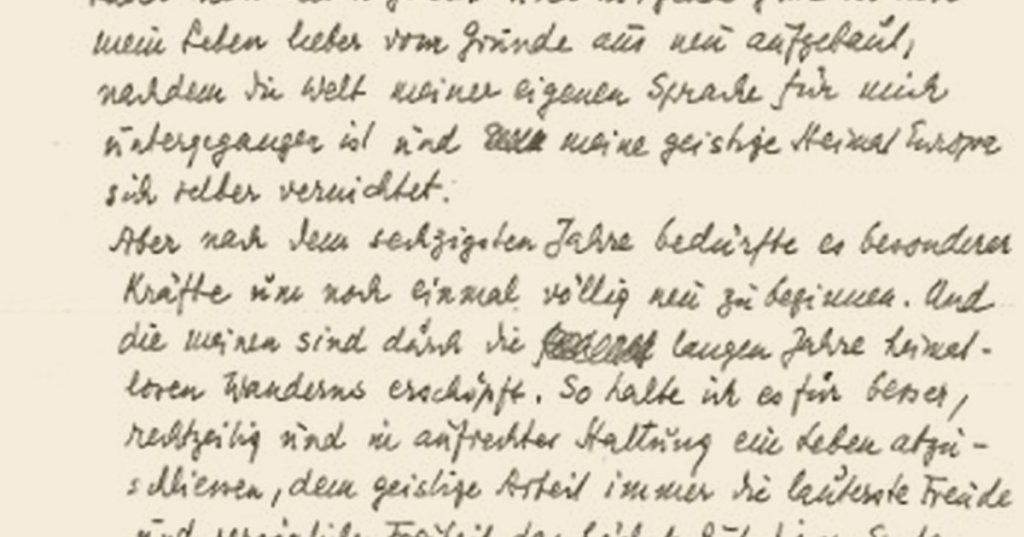

In 1942, living in Petrópolis, Brazil, Zweig died by suicide alongside his second wife, Lotte Altmann. The act was not a literary pose; it was the bleak endpoint of a long disillusionment as Europe fell into war and mass persecution. Yet the irony is sharp: the very qualities that made Zweig famous—clarity, empathy, psychological realism, and a sense of civilization’s fragility—also make him feel startlingly modern. His work reads like a warning and a consolation at the same time.

About This Book

The Stefan Zweig Collection – Volume 2: A New Translation gathers more of Zweig’s fiction and/or shorter works into a single volume aimed at contemporary English-language readers. If you’ve only encountered Zweig through quotes, a film adaptation, or a single famous novella, a collection is where you start to understand his range: the way he can compress obsession, guilt, desire, or moral compromise into scenes that move like clockwork. His stories often begin in ordinary rooms—train compartments, boarding houses, drawing rooms—and then quietly tighten until a character’s inner life becomes the real setting.

Why it matters now is not because it’s “important literature,” but because Zweig’s subject is the pressure modern life puts on the self. He writes about reputation and secrecy, about the moment a person realizes they are no longer steering their own choices, and about how social norms can turn intimate feelings into a kind of trap. In early 20th-century Europe, that trap might be class, propriety, or political fear; today it might look like status, visibility, or the relentless demand to perform a coherent identity. Zweig’s genius is that he doesn’t lecture—he dramatizes.

Why Read a Modern Translation?

A modern translation matters with Zweig because his power lives in tone: the quickening pace of a confession, the slight shift from calm observation to panic, the fine distinctions between shame, longing, and self-deception. Older English versions can feel stiff or overly formal, smoothing out the urgency that makes his narratives so addictive. A new translation typically aims for cleaner momentum and more natural dialogue while still preserving Zweig’s elegant psychological shading—exactly what you want in stories built on tension, nuance, and the feeling that one wrong sentence can change a life.

This Edition

This post contains affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases.

Leave a comment